Mastering the Art of Scientific Research: A Comprehensive Guide

Written on

Chapter 1: The Journey into Research

Over the years, I have been on a quest to enhance my research skills. While I am not yet an authority on the subject, I have gathered some helpful techniques along the way. My research experiences range from short essays exploring the explore-exploit dilemma and the impact of aging on learning, to in-depth projects like writing my book and a guide on motivation.

Research is vital for independent thinking. Without the ability to locate and comprehend the arguments of others, one may find themselves confined to their own intuition or the singular perspective of someone who caught their attention.

Although I don't consider myself a research expert, I wish to share my approach. This may help clarify my own thoughts and assist those eager to explore their curiosity but uncertain of where to begin.

Setting the Scope and Defining Your Topic

Unlike structured learning in a classroom, research is often open-ended. There is always another source—be it a book or a paper—that might offer valuable insights. Consequently, you may never reach a definitive endpoint.

This quality can make sustaining research efforts challenging. Our minds prefer tasks with clear completion markers, while open-ended inquiries may fizzle out due to their inherent lack of closure.

I recommend establishing a predetermined time commitment for your research. It's also beneficial to aim for a tangible outcome, such as drafting an essay, rather than allowing the insights to remain abstract. Writing compels you to organize your thoughts, retain important details, and ensure comprehension.

Beginning Your Research: Finding Key Concepts and Terms

Once you have a clear scope and topic, the next step is to identify the specialized vocabulary associated with your area of interest. Experts categorize subjects in ways that may not align with common understanding. For instance, if you wish to explore the concept of discipline, you’ll discover distinctions among terms like self-control, self-regulation, vigilance, and grit. These distinctions can signify nuanced ideas or represent different domains governed by varying methodologies and experiments.

Wikipedia can be a useful starting point, as it often bridges everyday language and expert terminology. Input your idea in plain English on Wikipedia, and take note of the expert terms and concepts that emerge.

Armed with relevant keywords, you can begin to pinpoint foundational works. What texts are widely acknowledged as pivotal in this field? Which ones provide a comprehensive overview without necessitating extensive reading?

Literature Review, Meta-Analysis, and Textbooks

After identifying key terms and possibly some seminal papers or authors, I typically seek out reviews of the field. Specifically, look for:

- Literature reviews, which qualitatively summarize all relevant papers on a subject.

- Meta-analyses, which quantitatively synthesize results from numerous studies to provide comprehensive answers.

- Textbooks, which are designed to instruct newcomers and present the field from an expert’s perspective.

A good starting point is Google Scholar. Enter a keyword you’ve identified along with the terms “review” or “meta-analysis” to see the results. For example, if “testing effect” emerged as a key concept from Wikipedia, you might search for “testing effect review” or “testing effect meta-analysis.”

For textbooks, I often utilize Amazon, inputting the relevant keyword and filtering for textbooks. For my latest project on apprenticeship, I reviewed all available textbooks with “apprenticeship” in their titles, reading numerous Kindle previews and subsequently a couple of full books.

Whether to begin with review articles or textbooks depends on the breadth of your inquiry. Textbooks are typically advantageous for broad topics, while review articles are better suited for specialized subjects, although there is some overlap.

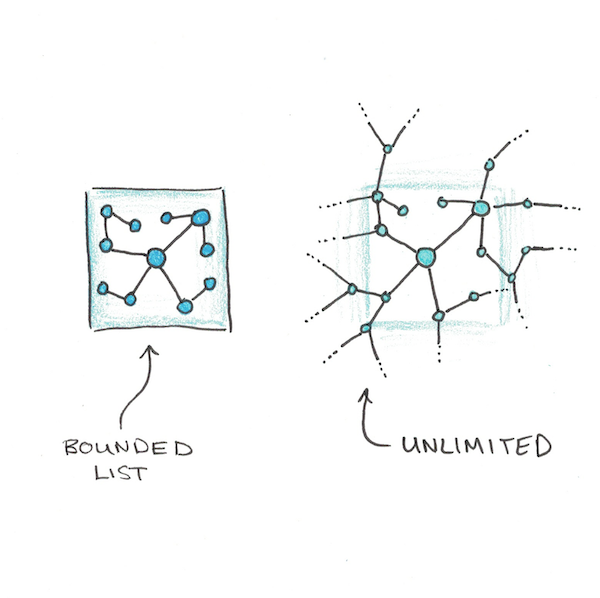

Following Citation Trails

Once you have established a foothold in a field, the next step is to follow citation trails. Given that any paper may reference dozens or even hundreds of other works, this can lead to a rapidly expanding reading list. Therefore, I usually focus on a few promising citations initially, unless I encounter a dead end.

When tracing citations, I consider two aspects: frequency and relevance. Works that are frequently cited tend to be more central to the field. If I notice a particular paper, book, or author appearing multiple times, I will download it even if it doesn’t seem directly related to my initial inquiry. I also make sure to follow up on any references that directly tackle my specific questions.

This stage typically consumes most of my research time. Generally, I prefer a breadth-first approach over a depth-first one, as it is easy to get lost in one line of inquiry and overlook alternative viewpoints. However, I don’t strictly adhere to this; sometimes, delving deep into a specific area can yield rich insights that answer unforeseen questions. In fact, I have added entire chapters to my book because the research was too valuable to leave as mere footnotes.

How to Effectively Read Research

I once inquired about research methods from Bryan Caplan, whom I admire for his rigorous argumentative style. He mentioned that he reads all available papers and then revisits them just before writing.

A common challenge in research is forgetting what you’ve read or where you encountered it. Some people utilize elaborate systems like Zettelkasten to combat this, though I find them less effective, perhaps due to my own ineptitude with such methods.

Instead, I prefer Caplan’s strategy. I read extensively, highlighting sections that may require revisiting later. After completing a book or substantial paper, I often create a new document to pull notes and quotes from my initial reading, alongside my best effort to summarize the material from memory. This practice serves to reinforce retrieval and comprehension while also creating a trail of breadcrumbs for future reference.

Some degree of re-reading is often necessary, particularly when tackling larger projects. My philosophy is not to memorize every detail but to acquire a general understanding of the subject area, allowing you to know where to find specific information when needed. Ideally, the primary findings in the field will stand out, even if you can’t recall every fact verbatim.

Additional Tips and Techniques

Beyond this foundational approach, several additional tools have proven beneficial:

- Utilize Sci-Hub for accessing papers. While I typically do not endorse copyright infringement, the current landscape of academic publishing often warrants skepticism towards publishers who profit from scientific work. Alternatively, reaching out to authors directly can sometimes yield access to papers, although this may slow your progress.

- Use Google Books to locate notes in printed texts. This was particularly useful when I wrote my last book. For instance, if I wanted to find something in my lengthy Van Gogh biography, I could peruse the index, but searching the book on Google was often more efficient.

- Map out key arguments and contributors. In some cases, the question you wish to address may already be resolved by scientific consensus. More often, however, you will encounter a range of differing viewpoints defended by various factions. I frequently find it advantageous to chart out the key positions and proponents, as this is where significant intellectual debates occur.

- Don’t hesitate to take preliminary courses. Engaging with a field through reading is akin to joining an ongoing discussion that has been in progress for centuries. The extent to which you need to backtrack and grasp foundational topics before effectively interacting with the material varies by discipline, but taking courses can provide valuable context.

- Experts are often surprisingly approachable. I was taken aback by how many busy professionals were willing to discuss their work with me. For instance, K. Anders Ericsson kindly reviewed my entire manuscript, offering feedback on sections related to deliberate practice.

Evaluating the Trustworthiness of Literature

I have not yet delved into the topic of assessing the reliability of literature itself. Determining what experts believe to be true is challenging enough without questioning the veracity of those beliefs. While my skills in this area are limited, "How to Read a Paper" provides a solid introduction to evaluating research. However, due to the replicability and generalizability issues prevalent in many fields, it is prudent to remain cautious, as today’s consensus may become tomorrow’s misconception.

The first video, "How to Pick a Science Research Topic & Idea: FULL GUIDE - YouTube," offers a comprehensive overview of selecting an appropriate research topic and refining your ideas for better clarity.

The second video, "How to Write a Scientific Research Paper - part 1 of 3 - YouTube," provides valuable insights into structuring and writing a scientific research paper effectively.