Did Ice Age Horses in America Sport Stripes Like Zebras?

Written on

Chapter 1: The Enigma of Ice Age Horses

Did the Ice Age horses of North America have bold black and white stripes reminiscent of zebras? Many popular illustrations may not accurately represent these ancient equines. These horses coexisted with mammoths, yet no living human has encountered the species that once roamed America towards the end of the Ice Age. Extinct alongside magnificent creatures like the Smilodon, these horses left no direct descendants. For thousands of years after their extinction, North America was devoid of horses, until settlers arrived with domesticated breeds. So what did these long-gone horses truly look like?

The last time I moved, our U-Haul truck showcased a graphic of a giant zebra head, or so it appeared! In reality, it was an artistic representation of the Hagerman horse, a species whose remains have been frequently unearthed in Idaho. Initially, I mistook the graphic for a zebra from Africa! The striking black and white stripes are iconic and unmistakable. The accompanying article on the company’s website was equally intriguing, posing numerous questions. Were the Ice Age horses in North America truly striped like zebras, or were they solid-colored, or perhaps a mix of earthy tones and patterns? Below, I sketched a quick representation of a potential brown-and-striped pattern for the Hagerman horse.

Could North America’s extinct Ice Age horses have looked like this? [Art by the author, dry media, 2022]

This article will explore three methods to make informed assumptions about the appearances of North America's Pleistocene horses, drawing conclusions from each type of evidence. The structure of their teeth, genetic studies, and cave art can provide significant insights.

Section 1.1: A Rich History of Equines in North America

North America can be seen as the birthplace of horses, having witnessed a remarkable variety of equine species over time. Wyoming, for instance, is home to a treasure trove of fossils belonging to Hyracotherium, known as the earliest horse or “eohippus.” In the past, smaller, three-toed grazers coexisted with creatures like hell pigs and sabertooth predators. Meanwhile, during the Ice Age, Equus horses, resembling modern breeds, galloped across the continent. Even larger horses, part of the Equus genus, thrived in Texas and other prairie regions. The continent has served as a sanctuary for horses through the ages. Unfortunately, this diverse equine community dwindled, culminating in the extinction of the last horses in the Americas around the same time as other megafauna such as mammoths and dire wolves. The lineage of horsekind in the Americas was abruptly severed.

Today's wild horses, however, have a narrative intertwined with European settlers. Early colonizers reintroduced horses to the landscape, where they quickly adapted and became pivotal to various Indigenous cultures. Feral horse populations have existed for centuries, and these wild equines became emblematic of the American West. Beneath their galloping hooves lie the ancient fossil remains of the horses that once roamed these lands, now extinct. Present-day horses trace their ancestry back to breeds first domesticated in Eurasia, yet they remain close relatives, all within the Equus genus.

Chapter 2: Decoding the Appearance of Ancient Horses

In the video titled "Ice Age Horse? Old But Not Quite," we explore the fascinating evidence surrounding the appearance of horses during the Ice Age, including their potential coloration and patterns.

We have yet to uncover paleoart depicting the horses of America, leaving us with many uncertainties about their appearance. Paleontologists and artists face numerous challenges in depicting these ancient animals accurately.

One potential starting point is to examine the Pleistocene Equus through their teeth, a crucial piece of evidence left scattered across the continent.

Here, we see a Pleistocene fossil horse tooth (photo by the author). By examining the surface of the molar that contacted food, we can identify which species it represents. The Florida Museum of Natural History provides a compelling comparison of various horse teeth, including a diagram that aligns closely with my fossil tooth.

Interestingly, the fossilized teeth align remarkably with those of zebras! Zebras have distinctive stripes, and even the quagga, which lacks full-body stripes, prominently displays markings on its front. Consequently, the Florida Museum depicts Equus simplicidens with striking black and white stripes, similar to how U-Haul portrayed it as the long-lost counterpart of African zebras.

While the evidence from teeth may suggest a straightforward conclusion, the narrative becomes more complex when we consider the prehistoric horses depicted in European cave art. These horses do not resemble zebras and often appear with a dun coloration, lacking prominent stripes. Additionally, we can analyze more than just skeletal remains, as horses and zebras share many similarities.

A second method for analyzing ancient horse coloration involves examining specific genes preserved in horse fossils. Fortunately, these horses lived relatively recently, allowing for DNA analysis. Recent studies reveal that North American horses interbred with Eurasian populations, particularly through the Bering Land Bridge, both before domestication and during the Late Pleistocene. This suggests that the horses inhabiting North America were likely not a separate species. Genetic mutations moving between the continents imply that Ice Age horses were a globally connected species, with regional populations freely breeding during migrations.

This revelation is significant, as it suggests that Equus simplicidens, also known as the Hagerman horse or American zebra, and Equus ferus, the wild horse from Eurasia, may be the same species or at least more closely related than previously believed.

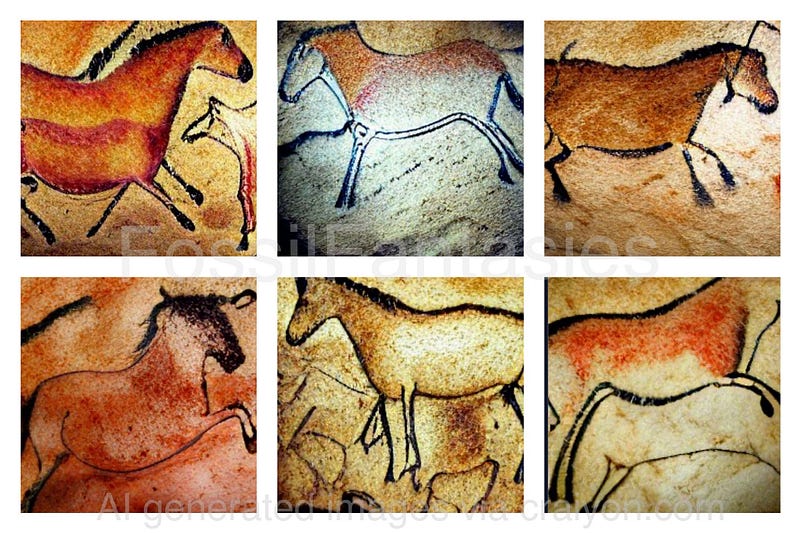

The third approach to understanding ancient horse pigmentation is through the lens of human history, specifically the cave art created by our ancestors. Horses are prominently featured in many cave art sites across Europe, often making up nearly one-third of the depicted creatures. Many of these horses appear to have a dun-colored coat, characterized by a brown body, dark dorsal stripe, and “zebra stripe” leg markings. There are also indications of varied patterns, suggesting that horses might have had black or spotted coats during that era. However, none of the cave paintings exhibit the iconic black and white stripes characteristic of zebras.

Imagine the striking visuals if prehistoric horses indeed sported zebra-like stripes, and how significant it would be to discover detailed depictions of such horses in the Americas!

Some theorize that horses worldwide were primarily striped until domestication began, suggesting that solid colors became a bred trait to make domestic animals easier to locate in the wild. Most reliable sources indicate that horse domestication occurred relatively recently, around 5,000 to 6,000 years ago, whereas the cave paintings showcasing horses in various colors are significantly older. Thus, these horses must have been wild unless domestication predated our current understanding. However, it has been noted that genetic variations for new coat colors began to emerge around the same time as domestication.

In conclusion, it appears likely that the horses of Ice Age North America did possess stripes. At the very least, they probably had a dorsal stripe and leg markings typical of dun-colored horses. Given the genetic interbreeding with Eurasian Equus, it stands to reason that these horses shared physical similarities, even with regional differences. While it is difficult to provide a definitive answer, scientific research allows us to make educated guesses. I believe the American horses did not resemble full-body striped zebras but likely shared some striping features, similar to their genetically close European relatives, which often had dun coats with fewer stripes.

This small watercolor painting above was a gift for my horse-loving sister. While I imagined the horse with clear leg stripes, the subtler stripes I attempted on the head were lost in shading. Although this artistic representation is merely speculative, future developments may provide clarity on the appearance of Pleistocene horses in North America. Genetic analysis has already indicated how Eurasian horses’ coats were patterned, and it has also demonstrated that North American Equus horses were not isolated, distinct species but interconnected with those on other landmasses.

Given the genetic flow of Ice Age horses and the wealth of cave imagery depicting Eurasian horses, I believe that the portrayal of American Pleistocene horses as black-and-white-striped zebra lookalikes is likely inaccurate. They probably had stripes, especially on their legs, but depicting them as fully striped is an exaggeration. Future studies may investigate the genes responsible for coat colors and patterns in horse fossils found in the United States and Canada, potentially answering the question of whether Ice Age horses in the Western Hemisphere had zebra-like stripes.