# The Astonishing Discovery of Pulsars: Jocelyn Bell's Journey

Written on

Chapter 1: The Signal That Shook Astronomy

On November 28, 1967, a young graduate student at Cambridge University captured a mysterious signal that she whimsically named ‘Little Green Men-1’ or ‘LGM-1.’ This discovery wasn't a mere joke; it sent shockwaves through the astronomy community, sparking widespread discussion.

These signals were detected with the Interplanetary Scintillation Array at the Mullard Radio Astronomy Observatory, originating from a star that would later become a central topic for physicists eager to bridge Quantum Mechanics with General Relativity. What celestial objects became crucial in testing these theories? Why was the graduate student overlooked by the Nobel Committee despite her significant contribution? And how did this instance exemplify serendipity in scientific discovery? Let’s explore the life of Jocelyn Bell, the scientist who initially misidentified these signals as coming from an extraterrestrial civilization.

Jocelyn Bell was born on July 15, 1943, in Armagh, Northern Ireland. Her father, an architect, played a role in constructing the Armagh Planetarium, which sparked Jocelyn's interest in astronomy from an early age. Inspired by her father's astronomy books and the encouragement from planetarium staff, she resolved to dedicate her life to radio astronomy.

In a male-dominated field, Jocelyn stood out as the only woman in her 50-student B.Sc. class in natural philosophy (Physics) at the University of Glasgow. During a time when girls were often relegated to traditional roles, Jocelyn was fortunate to have a supportive family that encouraged her ambitions. She eventually excelled enough to gain admission to Cambridge University’s PhD program.

Despite her achievements, Bell grappled with Imposter Syndrome, doubting her place at Cambridge. To counteract these feelings, she dedicated herself to her studies, working diligently on a radio telescope known as the “Interplanetary Scintillation Array.” During that era, quasars were the hot topic in astronomy, and this telescope was designed to detect their signals.

Bell, along with her peers, constructed a massive radio telescope, involving the installation of approximately 1,000 posts and 2,000 dipole antennas connected across 120 miles. After nearly two years of labor, the telescope was finally operational. However, as often happens in science, the most remarkable discoveries come from unexpected directions.

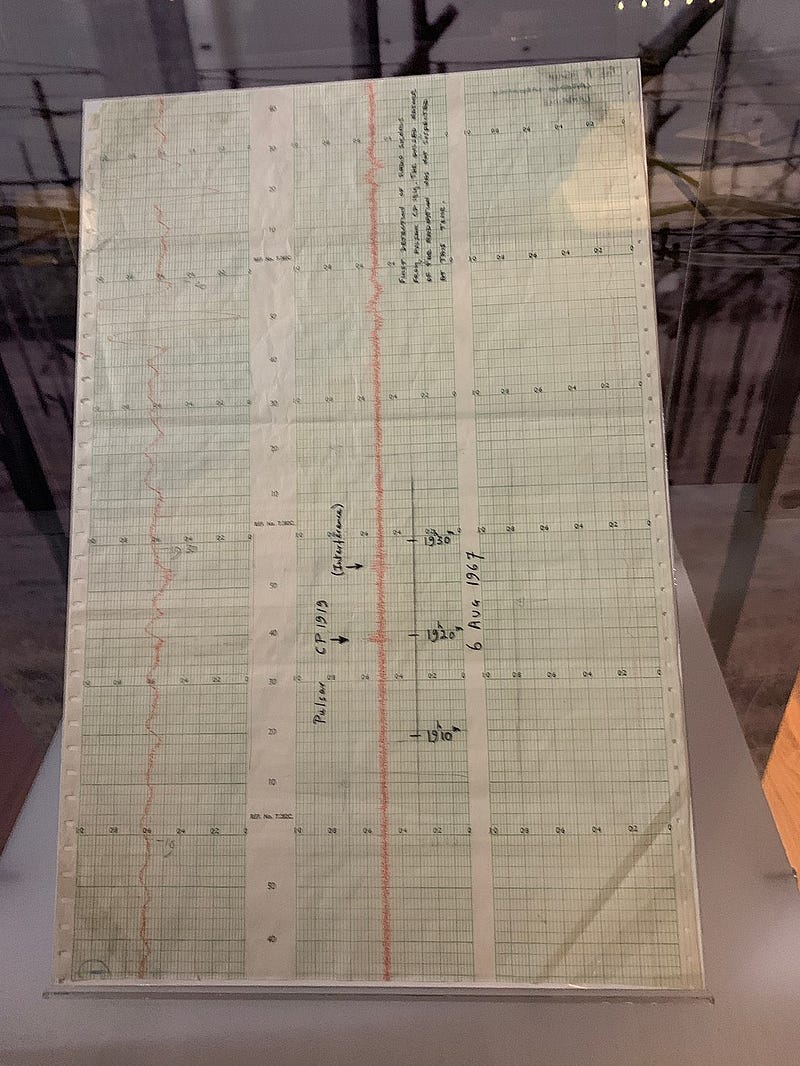

Jocelyn was responsible for scanning the sky with this newly built instrument, alongside her PhD supervisor, Anthony Hewish. By July 1967, she began analyzing the data, going through nearly 100 feet of paper daily to identify scintillation or interference patterns. One day, she observed a peculiar signal repeating every 1.3 seconds from a specific region of the sky. When she presented her findings to Hewish, he dismissed the possibility of a groundbreaking discovery, suggesting it was improbable for a star to emit signals at such regular intervals. They considered potential sources of interference, from other radio astronomers to radar reflections. Ultimately, they jokingly referred to the signal as the “Little Green Men” signal due to its bizarre nature.

Thanks to her meticulous approach, Jocelyn eliminated technical issues that might yield false positives. The mysterious signals returned, now with intervals of 1.2 seconds from another region of the sky. This time, Hewish took them seriously, directing Jocelyn to extend her recordings. The new data further debunked the alien hypothesis, as it seemed too coincidental for two distinct extraterrestrial sources to be sending signals simultaneously.

These signals turned out to be groundbreaking discoveries in astronomy: pulsars—rapidly rotating neutron stars that emit powerful electromagnetic beams from their magnetic poles. Walter Baade and Fritz Zwicky had predicted the existence of neutron stars shortly after James Chadwick discovered neutrons. However, not all supernovae result in neutron stars; the core must possess a certain mass for the transformation to occur. Neutron stars have magnetic fields a trillion times stronger than Earth's and can rotate astonishingly fast, with some spinning 716 times per second.

Despite her pivotal role in this discovery, Burnell was largely overlooked. The Nobel Prize was awarded to Hewish and Ryle, while the media focused on Burnell's personal life rather than her scientific contributions. Many, including Fred Hoyle, criticized the Nobel Committee for excluding her from recognition. Jocelyn herself expressed understanding, noting that it was rare for a graduate student to receive such an honor, and she found peace with the committee's decision.

Chapter 2: The Legacy of Jocelyn Bell

The first video, "Scientists Stunned as Ancient Alien Signal Reaches Earth for First Time," delves into the implications of ancient signals and their potential extraterrestrial origins.

The second video, "Messaging The Aliens, Moving the Earth, Shapes of Coronagraphs | Q&A 258," explores the broader themes of communication with potential alien civilizations and the scientific advancements that accompany such inquiries.