Exploring the Rise of Psychedelics in Mental Health Treatment

Written on

Psychedelic treatments are becoming increasingly popular as innovative solutions for trauma and depression, unlocking critical periods in the brain. However, the exact mechanisms of these substances remain largely unknown.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many individuals in Argentina and across the Western world turned to common hobbies to alleviate boredom—sourdough baking, TikTok dances, yoga, and small apartment marathons. Yet, when confinement restrictions eased, a newfound interest emerged in the previously taboo practice of microdosing psilocybin. Traditional hobbies faded, while psychedelics gained prominence, signaling the beginning of a new trend.

## Understanding Psychedelics

For centuries, various indigenous cultures have utilized natural psychedelics, including psilocybin from mushrooms, peyote from cacti, ayahuasca from Amazonian plants, and ibogaine from African shrubs. These substances were employed for spiritual communication, healing, and fostering unity and broadened perspectives.

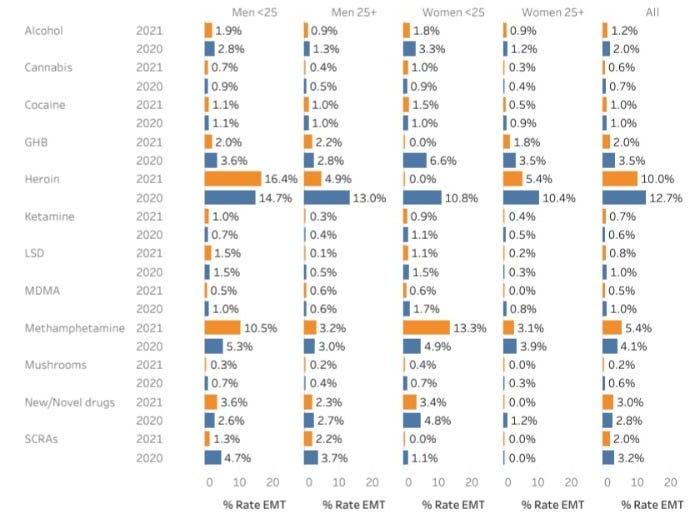

Research into the antidepressant properties of psychedelics, including synthetic compounds like ketamine and LSD, flourished in the mid-20th century. However, many nations subsequently banned these substances, stalling further investigation. The counterculture movement of the 1960s brought attention to psychedelics, but also led to their stigmatization. Interest has recently surged since the early 2000s, with clinical trials revealing that ketamine and MDMA can rival conventional psychiatric medications. The urgency for new therapeutic options has intensified in the wake of the pandemic, amid rising rates of depression and opioid addiction.

From a pharmacological standpoint, the term "psychedelic" typically refers to hallucinogenic substances like psilocybin and LSD, which bind to the 5-HT2A serotonin receptor on neurons. Although THC, the primary component of cannabis, is sometimes included in discussions of psychedelics, it does not fit the traditional definition. The lack of standardized definitions and protocols complicates research into these substances.

## The Mechanics of Psychedelics

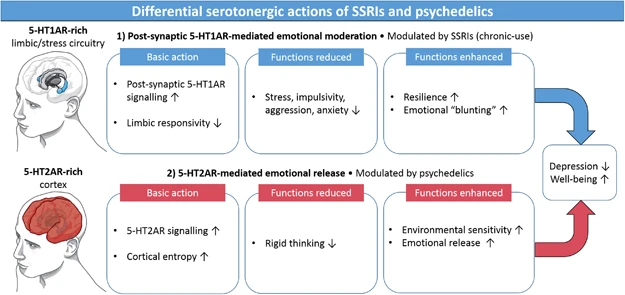

Psychedelics such as ketamine and MDMA influence the brain broadly, interacting with numerous neurons and molecules. Classical psychedelics like LSD and psilocybin engage more than just the 5-HT2A receptor, although the primary receptors responsible for their psychiatric benefits are still debated.

In psychiatry, psychedelics are transitioning from fringe to mainstream acceptance. Oregon's legalization of psilocybin in 2019 paved the way for the first treatment center, while the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies is pursuing FDA approval for MDMA to treat PTSD, a move anticipated to succeed due to clinical evidence and public support.

Legal research into psychedelics is gaining momentum, driven by evolving regulations and potential profitability. Nevertheless, the precise workings of these substances remain elusive, obscured by their historical illegality and the complexities of studying psychiatric conditions in animal models. Nevertheless, David Olson, a biochemist at UC, suggests that a deep understanding of psychedelics isn't always necessary for effective therapy.

## Psychedelics and Brain Function

Research from the University of Helsinki indicates that psychedelics like ketamine and psilocybin can induce rapid and lasting antidepressant effects, promoting neuroplasticity—an ability to form new neural connections. Conventional antidepressants such as Prozac bind to the serotonin receptor, but psychedelics may exert their effects with significantly greater potency, leading to quicker symptom relief.

Scientists generally agree that psychedelics enhance neuroplasticity, which may help reshape perceptions for individuals with depression or assist those with PTSD in dissociating traumatic memories from fear responses. However, the specifics of this neuroplasticity remain contentious, and the implicated brain regions are still under debate. Psychedelics, despite their marketing, come with potential drawbacks, as excessive plasticity can lead to conditions like autism and schizophrenia.

Neuroscientist Gül Dölen posits that psychedelics might not directly influence plasticity but rather enable metaplasticity, making neurons more receptive to stimuli that induce plasticity, such as hormones. Research on mice suggests that psychedelics can reopen a "critical period" for neural remodeling, highlighting the significance of social interaction and reimagining traumatic memories in reshaping neuronal connections.

## The Potential of Psychedelics

Psychedelics may serve as a "master key" to unlock critical periods in the brain, as noted by Gül Dölen. While this increased sensitivity to stimuli could be beneficial, an excess of metaplasticity might be harmful, akin to "melting the brain" and disrupting well-established neural connections, resulting in issues like seizures or memory loss. The context in which psychedelics are used is crucial; solitary use is not advisable.

The implications of psychedelics extend beyond mere therapeutic applications; they may aid in sensory recovery, skill acquisition, or language learning in conducive environments. They also show promise in treating various addictions, including to opiates and alcohol.

Dr. Rachel Yehuda's studies on PTSD with MDMA and psilocybin underscore the importance of the hallucinogenic experience in facilitating discussions about trauma. She notes, however, that similar epigenetic changes can arise from psychotherapy alone, suggesting that the drug may enhance therapeutic outcomes.

Researcher David Olson asserts that substances like ibogaine, which do not produce hallucinogenic effects, can still demonstrate neuroplasticity enhancement and mood improvement. This indicates that while some individuals may benefit from transformative experiences, others may find sufficient improvement through neuronal growth alone.

The definitive answers regarding psychedelics and their effects await further clinical investigation.

## The Challenges of Testing Psychedelics

Testing psychiatric medications against placebos presents unique challenges, especially for drugs that produce intense effects. In MDMA trials, the FDA has implemented a protocol where independent psychiatrists evaluate symptom improvement without knowledge of which patients received the drug.

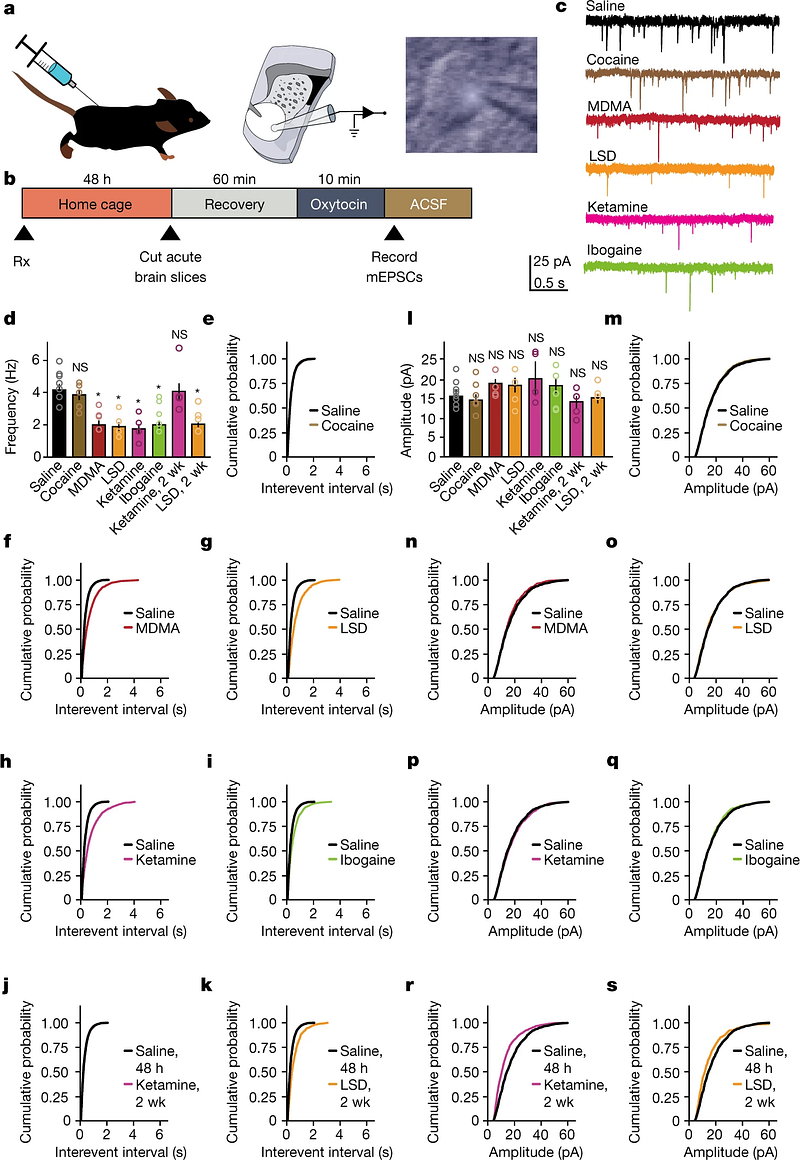

A study by Heifets et al. that examined ketamine in surgical patients found that those on placebos showed symptom improvement if they believed they might receive the drug, suggesting that anticipation itself can influence mood. This phenomenon highlights the importance of expectations in symptom management.

The real challenge in research lies in developing derivative drugs that target the same brain pathways as psychedelics, potentially yielding benefits without the accompanying hallucinogenic experiences.

While pharmaceutical companies cannot patent LSD, they can create new drugs with known mechanisms that mimic its effects. However, concerns about abuse remain, particularly with party drugs like ketamine and MDMA.

## A Personal Experience with Psychedelics

I admit I have embraced the trend of using psychedelics, although I’m not a frequent user. I enjoy the creativity and enhanced perception that psilocybin offers. I cultivate my own mushrooms, appreciating their origins and care. Once harvested, they wait in my fridge until I’m ready to explore new dimensions of my consciousness. I ensure I’m in a supportive environment when I use them, opting for micro-doses rather than large amounts.

Regardless of where the psychedelic movement leads, I believe these substances are valuable tools for understanding the brain and mind. When I experience them, I visualize my brain as a downloading bar, receiving new information that was previously inaccessible. Research shows that classic psychedelics such as LSD and psilocybin are not addictive—though LSD may induce tolerance—while mushrooms are considered among the safest options. Many of the fears surrounding substances like Ecstasy or acid causing lasting brain damage are unfounded.

The pressing question is how to responsibly liberalize existing prohibitions without jeopardizing the gradual acceptance of these substances in mainstream society. More research is essential to unravel the intricacies of their mechanisms, potential applications, and side effects. Despite the growing interest in microdosing and psychedelic experiences, a comprehensive understanding of how they function remains elusive.

Note: Avoid using psychedelics in isolation.