# The Multiverse as Inspiration: Quantum Mechanics and Modernism

Written on

Chapter 1: The Concept of the Multiverse

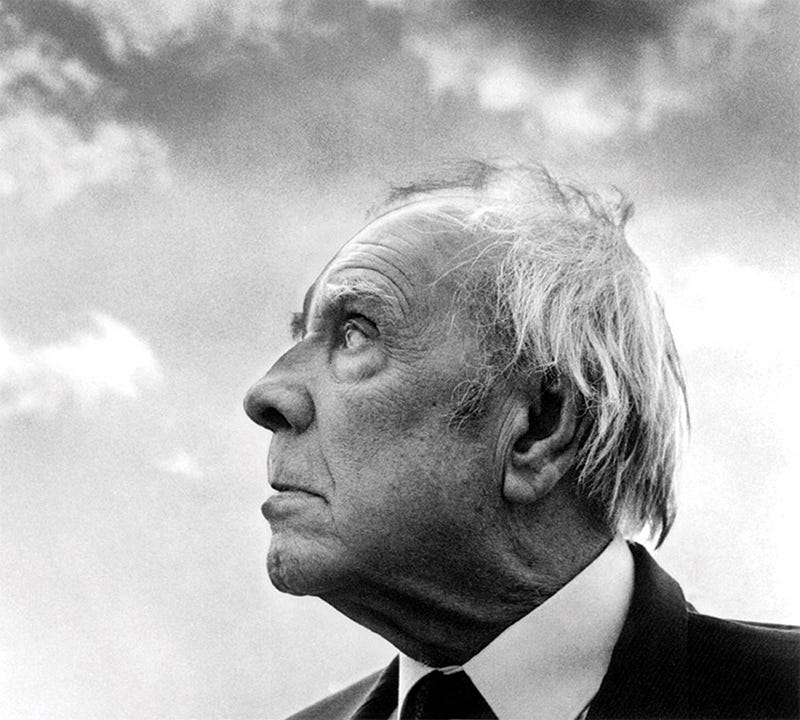

In the short story “The Garden of Forking Paths,” Argentine author Jorge Luis Borges envisions a present moment that can split into multiple futures—creating an endless maze of realities. He describes this as “an infinite series of times,” forming a complex web of diverging, converging, and parallel timelines. This tapestry of time includes all possibilities: in some, we do not exist; in others, you exist, but I do not; and in yet others, we both exist.

Borges imagined this intricate garden in 1941, a full 11 years prior to Erwin Schrödinger's notable lecture in Dublin regarding the various outcomes of his equations and the notion that parallel universes might all coexist simultaneously. It wasn’t until 1957 that Hugh Everett formally introduced the many-worlds interpretation of quantum physics, a theory that mirrors the forking paths in Borges's narrative. However, it took over a decade for the scientific community to genuinely consider this theory, by which time Everett had shifted away from theoretical physics and tragically passed away in 1982.

Although today's interpretations of the quantum multiverse often reference Everett, they can also be traced back to Modernist philosophy that emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Historically, the idea of the multiverse was rooted in religious thought, aiming to affirm the existence of God and his kindness, as illustrated by German philosopher and mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. This spiritual context is evident in earlier literary portrayals as well; for example, the many worlds and branching narratives in William Blake’s The Four Zoas, composed in the late 1700s to early 1800s, create a sort of multiverse that is also deeply spiritual.

In fact, the term “multiverse” was first introduced by American psychologist William James in 1895 to describe human experience and to reinforce faith in God. James noted, “Visible nature is all plasticity and indifference,” referring to the chaotic and incomprehensible aspects of the natural world. In his view, our existence amounts to a multiverse; it can only be perceived as a coherent universe when given deeper meaning.

For James, “multiverse” signified a multitude of experiences rather than the many worlds concept understood by contemporary physicists, philosophers, and writers. The modern multiverse is considered a natural outcome of established laws rather than a mere qualitative description. Andrei Linde, a physicist at Stanford University, explains that as the universe expands, it births new universes, making the multiverse akin to an ever-growing cosmological fractal. “These ideas are part of regular physics,” he asserts, “not speculation.”

The multiverse concept is woven into the fabric of modern philosophy, literature, and physics. German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, for instance, inverted Leibniz’s notion of “the best of all possible worlds” by suggesting we inhabit “the worst of all possible worlds.” He argued, “Possible means not what we may envision in our imagination, but what can actually exist.” According to Schopenhauer, our world is arranged in a way that allows it to continue existing, albeit with great difficulty.

Schopenhauer’s ideas hint at the anthropic principle, which posits that the universe's physical properties—such as the cosmological constant or gravitational force—must align with the existence of observers who study these properties.

“On or about December 1910,” Virginia Woolf noted, “human character changed.” This shift also altered storytelling methods. The disillusionment following World War I propelled people to question Enlightenment ideals, leading to narrative structures that no longer adhered to the classical mechanics of Newtonian physics. The fragmented and non-linear narrative styles found in the works of Woolf, James Joyce, and T.S. Eliot reflect a reality that defies rational representation.

Readers of modern literature often navigate through references that lead to dead ends and confusing spatiotemporal dimensions. These textual multiverses emerge from the absence of a singular truth, manifesting as intricate intertextual mazes and stories within stories.

British philosopher Olaf Stapledon, who penned influential science fiction in the early 20th century, also explored the idea of a universe brimming with infinite possibilities in his 1937 novel Star Maker. The narrative follows a nameless character on a journey through the cosmos, ultimately meeting the Star Maker, who creates a multitude of universes as part of his experiments.

“In one inconceivably complex cosmos,” Stapledon wrote, “whenever a creature was faced with several possible courses of action, it took them all, thereby creating many distinct temporal dimensions and distinct histories of the cosmos.” This resonates strongly with Borges and Stapledon's exploration of the infinite, which can evoke discomfort yet continues to inspire writers like Italo Calvino, C.S. Lewis, and Philip K. Dick.

The innovative storytelling techniques employed by Stapledon and Borges were influenced by the rise of quantum mechanics. While they may not have been versed in the specifics of quantum theory, they were aware of the scientific upheaval occurring around them, particularly concepts like Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle and Schrödinger’s famous thought experiment involving a cat that is both dead and alive. Traditional classical mechanics failed to encompass the entirety of reality, and the uncertainty inherent in quantum mechanics served as a fitting literary framework for modernist ideas.

David Deutsch, a physicist at the University of Oxford, explains, “In previous physics, using Newton’s laws to predict an event—like the position of Jupiter—also revealed the path it took.” However, in quantum theory, especially in its early formulations, the mechanics were not straightforward, leading to a chaos that paralleled the insights of Borges and Stapledon in the post-World War I landscape.

It appears that the concept of the multiverse may have emerged in physics as early as 1927, during Schrödinger’s initial developments of quantum theory. Sheldon Goldstein, a mathematics professor at Rutgers University, notes that Schrödinger's wave equation could be interpreted as indicating the existence of multiple worlds. This interpretation, which Schrödinger later rejected, suggested that when experiments are conducted, all possible outcomes occur simultaneously.

While Everett may not have been aware of this historical context, the foundational insights of quantum mechanics undoubtedly shaped his work, leading physicists, as well as writers and philosophers, towards the concept of the multiverse.

Jordana Cepelewicz is an editorial fellow at Nautilus.