The Ingenious Journey of Alexander Graham Bell and His Invention

Written on

Chapter 1: The Birth of the Telephone

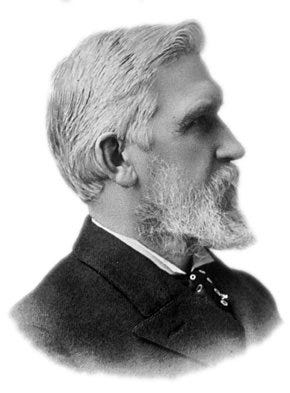

The telephone's invention is often credited to both Alexander Graham Bell and Elisha Gray. On March 14, 1876, Elisha Gray, a notable electrician from Chicago, rushed to the patent office to submit a caveat—essentially a legal notice declaring his intent to patent his invention, thereby preventing others from claiming it.

A few hours later, Graham Bell submitted a similar patent request. While Gray's device was technically superior, Bell's application was reviewed first due to his lawyer's prompt action. Gray's submission was not examined until the following day. Bell seized the opportunity; while Gray relied on the impartiality of the jury, Bell took the initiative to meet with officials directly, establishing a favorable rapport that ultimately led to his patent being approved.

Just three months later, Bell showed remarkable initiative. He realized that for his invention to gain popularity beyond scientific circles, it needed exposure. He attended scholarly gatherings, conferences, and exhibitions. Notably, during the centennial exhibition in Philadelphia, which showcased innovations like Remington's typewriter and Heinz's ketchup, Bell made a significant impression. Among the attendees was Emperor Dom Pedro II of Brazil, who initially showed great interest in Gray's musical telegraph. However, when Bell invited the emperor to witness his invention, he was captivated. Bell recited Shakespeare, and the emperor could hear every word through the device, a moment witnessed by numerous journalists. Following this triumph, Bell was awarded a gold medal, and he felt confident that his telephone would become a sensation.

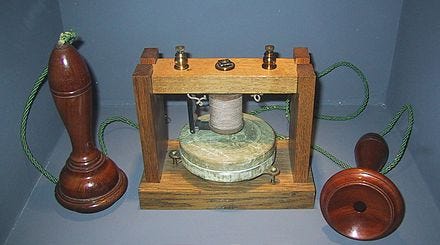

In just a few months since that pivotal day on March 10, 1876, Bell’s journey had been extraordinary. His famous words, "Mr. Watson, come here, I need you!" were not the fictional calls of Sherlock Holmes but rather a genuine request for help to test his prototype, known as a "vibraphone." This device operated in only one direction, necessitating awkward exchanges between Bell and his assistant. Fortunately, the patent office's decision to credit Bell with the invention allowed him access to Gray's designs, which he could use to enhance his own device.

After the summer of 1876, Bell continued refining his invention, replacing crucial components. By fall, he successfully communicated across a three-kilometer distance. It would take years of experimentation to establish the first long-distance line from New York to Chicago in 1892.

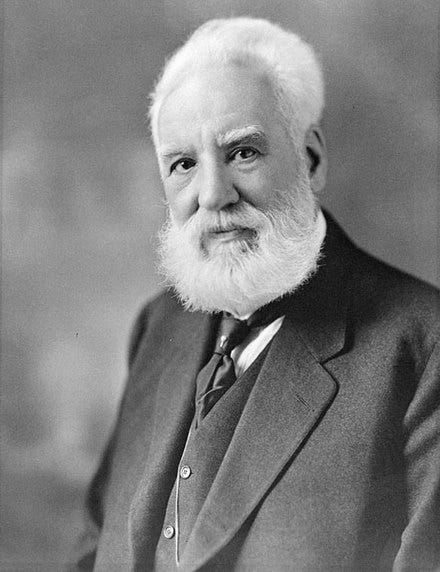

For Bell, success arrived, bringing both fame and wealth. However, this newfound fortune, combined with his fierce competition with Gray, often overshadowed his true character. Bell was not a mercenary businessman; he was committed to sharing the benefits of his invention with those he loved. On his wedding day, his wife received shares in the Bell Telephone Company, and his family enjoyed foreign rights to the invention. While the telephone would indeed secure his financial future, his greater passion lay in teaching. As a professor dedicated to educating deaf children, Bell was deeply moved by their struggles and worked tirelessly to improve their lives. He formed a close bond with Helen Keller, writing to her in Braille and assisting her in achieving her dream of attending school with peers. Keller regarded him as a father figure, expressing gratitude for his unwavering support.

To help identify hearing issues in children, Bell devised an auditory acuity test, the audiometer, a project he was proud of. He once stated, "I am more useful as a teacher of the deaf than I will ever be as an electrician." He recognized the challenges of invention but found joy in it. Teaching the deaf was his true vocation.

As he focused more on education and family, Bell gradually distanced himself from his invention, reflecting, "I have become so detached from the telephone that I wonder if I actually invented it or if it’s someone else I heard about." Nevertheless, his insatiable curiosity persisted. Even in semi-retirement before turning 40, Bell continued to innovate, sometimes working for twenty-eight hours straight on projects. "I have periods of excitement where my mind is teeming with ideas that flow to the tips of my fingers," he noted.

Bell's inventive spirit remained undiminished as he explored whimsical ideas. His wife Mabel remarked, "I have an incredible husband," as he constantly dreamed up new inventions. Watching seagulls soar inspired him to conceive flying machines integrated with telephones and torpedoes. Each quarter-hour, he would redesign his aircraft, and he often pondered the geological formations around him, conducting small experiments at home.

Even in his later years, Graham Bell remained an innovative and eccentric inventor, a curious dreamer who, as a child, found joy in nature and imagination, always pondering the next great idea.

Chapter 2: Learning from the Master

In this engaging video, viewers can learn about Alexander Graham Bell's life and contributions to the invention of the telephone, showcasing the challenges he overcame.

This video provides a captivating biography of Alexander Graham Bell, detailing his journey as one of history's most famous inventors and his impact on communication technology.