Exploring Ivermectin: Miracle Drug or Misguided Science?

Written on

Introduction to Ivermectin

Let’s discuss ivermectin.

From the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, various medications have been heralded as near miraculous solutions for the virus. Discussions regarding agents like hydroxychloroquine and lopinavir often descended into conspiracy theories, overshadowing rational scientific discourse. Advocates would accuse skeptics of concealing the truth about a safe and effective remedy due to pharmaceutical interests or hidden agendas. Conversely, skeptics would criticize proponents for flawed data interpretation and unrealistic optimism.

A pivotal moment in this dialogue involved ivermectin, particularly a meta-analysis of randomized trials conducted by Andrew Hill and colleagues published in Open Forum Infectious Diseases, which seemed to suggest significant effectiveness against COVID-19.

Understanding Ivermectin's Mechanism

To understand this fully, we must clarify how ivermectin works.

Ivermectin is primarily an anti-parasitic medication used to treat conditions such as scabies, river blindness, and filariasis. It has been in global circulation since its discovery in 1975 and is included in the WHO's list of essential medicines. The drug functions by binding to specific chloride channels in the nerve and muscle cells of parasites, effectively paralyzing them. While humans possess these channels, they are limited to our brains and spinal cords, and since ivermectin cannot penetrate the blood-brain barrier, we are not affected by its actions.

However, it's important to note that SARS-CoV-2 is not a living organism with muscles or nerves. So, what drives the interest in using this medication against the virus? Much of the enthusiasm stems from research indicating that ivermectin might exhibit anti-viral properties by interfering with a protein called importin, which many viruses exploit for replication.

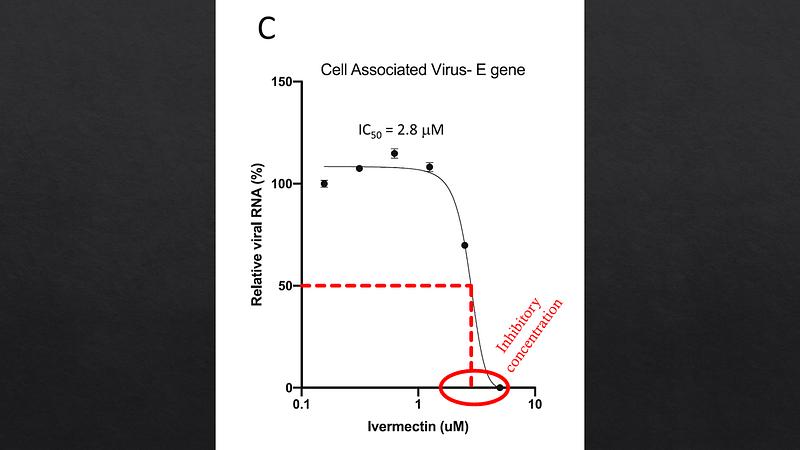

Researchers conducted experiments by infecting cell cultures with SARS-CoV-2 and introducing varying concentrations of ivermectin, observing a marked reduction in viral replication in a controlled environment.

Challenges in Real-World Application

Despite these findings, a critical issue arises. The concentration of ivermectin necessary to inhibit the virus in vitro, approximately 2.5 micromolar, is unattainable in actual human patients. Standard dosing results in blood concentrations around 25 nanomolar, which is 100 times lower than the levels required in laboratory settings. While lung concentrations may be slightly higher, they still fall short of the necessary thresholds.

Thus, if ivermectin is to be effective in treating COVID-19, it must operate through alternative mechanisms, possibly by reducing inflammation. However, the biological plausibility of this is questionable.

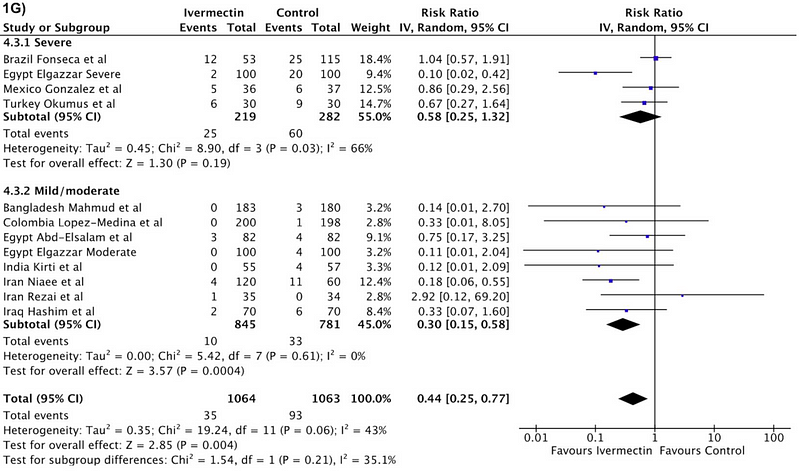

Numerous clinical trials have now explored ivermectin's efficacy against COVID-19, and according to the aforementioned meta-analysis, the findings appear promising. The authors compiled data from 24 randomized trials involving 3,328 patients to analyze various outcomes, with a particular focus on mortality rates.

Evaluating Meta-Analysis Results

In 11 trials, encompassing around 2,000 patients, mortality data was available. The results indicated a death rate of 3% within the ivermectin group compared to 8.7% in the control group, presenting a statistically significant outcome.

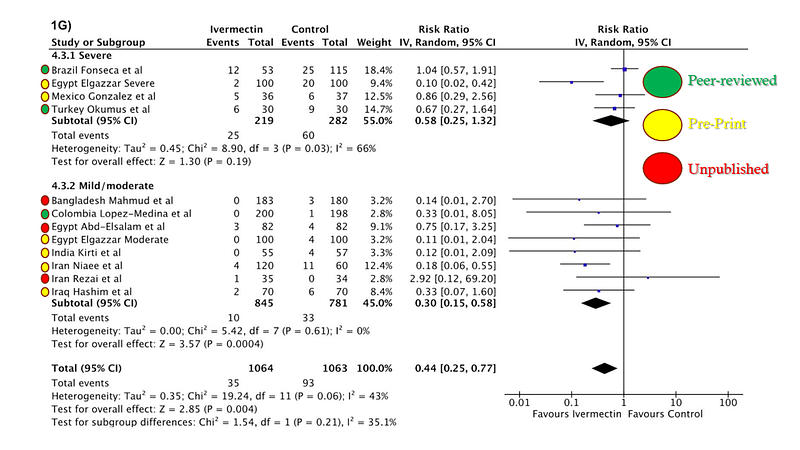

However, it’s crucial to approach these results with caution. The validity of a meta-analysis hinges on the quality of the included studies. This analysis amalgamated data from peer-reviewed studies, pre-print publications, and unpublished results from researchers interested in ivermectin.

Concerns About Data Integrity

A few issues merit attention. The inclusion of unpublished studies poses significant risks, as these results lack external validation. Researchers with promising data may be more inclined to share their findings, while those with less favorable outcomes might refrain.

While pre-prints can expedite information dissemination, peer review serves a critical purpose in validating findings. Some studies may never undergo publication due to intrinsic methodological flaws, not necessarily due to conspiracies against ivermectin.

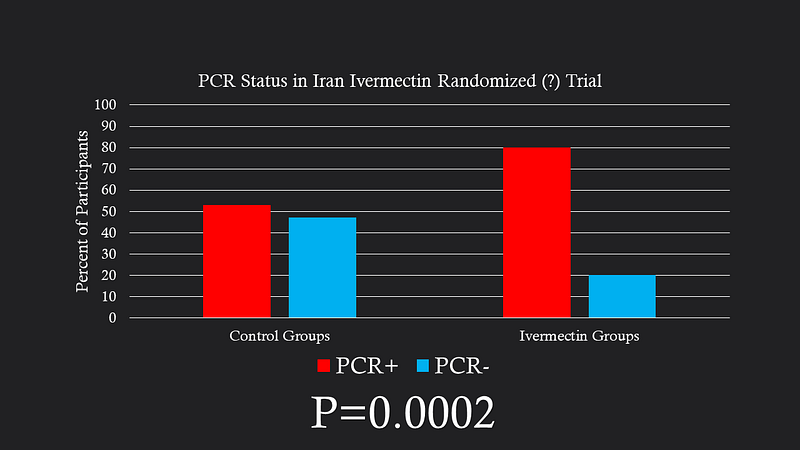

One notable trial contributing to the mortality benefit originated from Iran and was hosted on a pre-print server. This randomized study involved patients hospitalized with COVID-19, but it presented concerning discrepancies; 29% of participants tested negative for SARS-CoV-2, a figure that was notably higher in control groups.

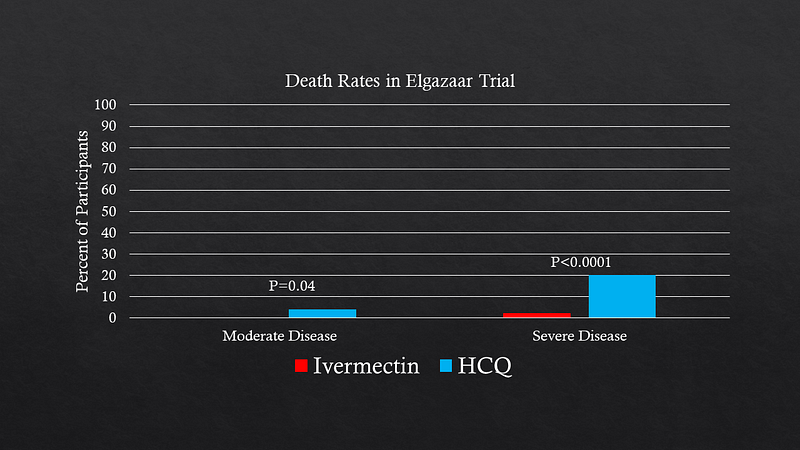

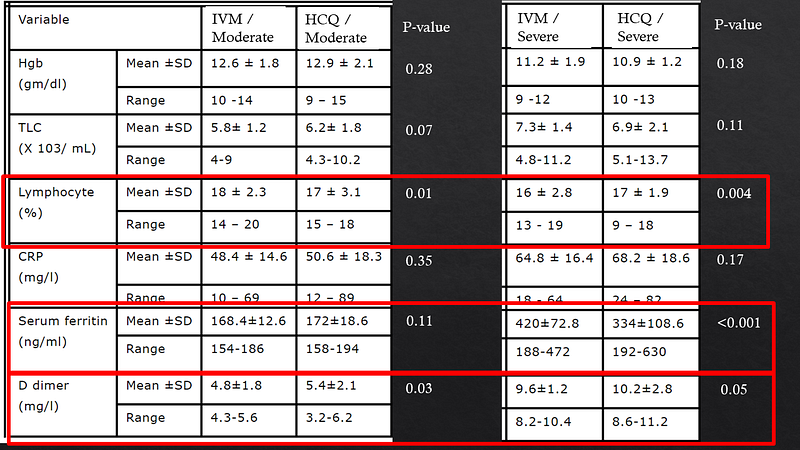

Another significant trial from Egypt compared ivermectin with hydroxychloroquine in 400 COVID-19 patients. The stark mortality differences observed raised questions about the validity of the results, especially given the lack of placebo control in the hydroxychloroquine group.

The necessity of peer review becomes evident, as it allows researchers to address potential flaws and improve the robustness of their findings. Some analyses suggest that excluding the Iranian and Egyptian studies diminishes the perceived protective effect of ivermectin, highlighting the ongoing uncertainty surrounding its efficacy.

What Comes Next?

While the simplest solution is to advocate for vaccination—rendering ivermectin unnecessary—this is not feasible in many regions where vaccines are unavailable, yet ivermectin is accessible.

In light of this, my proposal is that researchers involved in these trials should, for public health's sake, share not only their findings but also their analytical datasets in a de-identified format on platforms like datadryad.com. This would enable the broader community to assess the data directly, fostering transparency and informed decision-making.

We must unite, regardless of our stance on ivermectin, to advocate for data sharing during this public health crisis, ensuring that we can determine the true efficacy of this medication.

A version of this commentary originally appeared on medscape.com.